In this season of high stakes movie premiers, we saw the release this week of a highly anticipated video, one that riveted the nation as soon as it hit the Internet. This was not the latest installment of a Hollywood franchise, but the chilling twenty-seven minute body cam footage of the point-blank killing of Samuel DuBose by a campus police officer here in Cincinnati where I live. If you haven’t seen it yet, you can watch it here, but be prepared; the footage is disturbing. The video was released as part of an announcement detailing murder charges against the officer involved in the shooting, and it seemed probable that the ten-day delay in making the video available to the public was driven by the desire of authorities to have a narrative context in place—in this case, that a grand jury had indicted the uniformed shooter for murder and involuntary manslaughter—before allowing the public to process the experience of watching the video.

In this conjunction of the visual and the narrative, of wanting to provide an interpretive framework for a visual experience, the body cam footage of the murder of Samuel DuBose becomes an example of the cinema of everyday life. In referring to the video as “cinema,” I do not mean to trivialize the incident or to cast doubt on the importance of the video. Just the opposite, in fact. In the powerful reality effect of the video, prompting even the conservative, law-and-order Hamilton County prosecutor Joe Deters, whose office had justified many earlier police shootings, to declare that the shooting of DuBose was “”without question, a murder,” we can see how cinema has forever changed the way we experience and understand the world around us.

In short, the cinematic has become a central part of how we define reality. From the beginnings of cinema, the earliest screen experiences of the peep show and Kinetoscope directly engaged viewers in questions of the real. As I detail in Chapter One of Screen Ages, American cinema began with “actualities,” early forms of what we would call “documentaries,” that promoted themselves on the basis of recording the “actual.” But also from the beginning, these short films were just as fraught with as many questions of the manipulation and recreation of events as we see in critiques of reality TV and cable news today. And of course this reality effect bled over into “fiction” filmmaking as well, as in Edwin Porter’s Life of an American Fireman (1902), which combined footage of real fire departments in action with studio-shot scenes of a daring rescue.

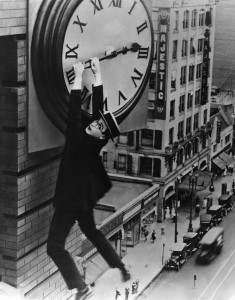

Cinema built on photography’s promise to “capture” visual reality, and this idea of reality caught on film /caught on tape/caught on video reverberates throughout cinema history in ways that again blur the lines between “fiction” and “non-fiction,” as in the long history of stunt work in the movies creating a sense of danger and risk, whether it’s Harold Lloyd crawling up the side of a skyscraper in Safety Last! in 1923 or Tom Cruise clinging to the side of a military transport plane taking off in this week’s Mission: Impossible–Rogue Nation. In more recent movies, this idea of action “caught” on camera has become it’s own cliché in the “found footage” genre of horror movies, from The Blair Witch Project (1999) to Clo

/caught on tape/caught on video reverberates throughout cinema history in ways that again blur the lines between “fiction” and “non-fiction,” as in the long history of stunt work in the movies creating a sense of danger and risk, whether it’s Harold Lloyd crawling up the side of a skyscraper in Safety Last! in 1923 or Tom Cruise clinging to the side of a military transport plane taking off in this week’s Mission: Impossible–Rogue Nation. In more recent movies, this idea of action “caught” on camera has become it’s own cliché in the “found footage” genre of horror movies, from The Blair Witch Project (1999) to Clo verfield (2008) and the Paranormal Activity (2007) series.

verfield (2008) and the Paranormal Activity (2007) series.

Maybe the most famous example of reality caught on film is the so-called Zapruder film of the assassination of John F. Kennedy from 1963. Shot on eight millimeter film and only twenty six seconds long, Abraham Zapruder’s historic amateur footage is also an example of the home movie explosion after World War Two, where (relatively) inexpensive cameras allowed millions of Americans to create their own screen experiences of their everyday realities. Today, of course, we would expect dozens of phone video recordings of the Kennedy presidential motorcade, all complete with sound and all uploaded almost immediately onto the Internet.

The Zapruder film also expressed the two parts of the cinema experience, as it both shows us the visual “reality” of the assassination and prompted a half-century’s worth of narratives meant to explain just what that reality is. Seeing is believing, but believing is also seeing, as the single Zapruder film became evidence for a wide range of interpretations, both supposedly proving and disproving that Lee Harvey Oswald acted as a lone gunman. Here’s the most famous cinematic representation of movie criticism as conspiracy theory, from Oliver Stone’s 1991 JFK. Kevin Costner as New Orleans DA Jim Garrison schools a jury in what the video “really” means as part of making the case for US government involvement in the assassination (and another warning: if you haven’t seen this before, the scene involves close-ups of the Zapruder film showing Kennedy’s graphic murder):

Stone combines the “real” Zapruder film with his own cinematic recreations of the event in various film stocks, in both color and black and white, some clearly meant to evoke “movie” footage, some to look like more “home” movies. Movie critics and historians have debated the ethics of what Stone is doing here, but there is no arguing with the power and importance of linking the visual and the narrative, what we see with what we should believe.

We can think of this double nature of the cinematic in terms of the difference between seeing and recording. When we view the world through our eyes, we always see with intention. We look “at” things, and we always have reasons for that looking (even aimlessly looking around is a kind of intention). The camera lens, on the other hand, records. It can be aimed (as both Zapruder and Stone were doing), but the camera itself has no intention. Everyone who takes pictures with their mobile phone experiences this difference when the picture we take doesn’t look like the scene we saw in front of us, or when the photo on the driver’s license doesn’t match how we see ourselves. And it’s not just photos of ourselves; most of us have seen pictures of our friends that we think don’t look like them.

In the case of the body cam, the camera is even more unmotivated; its aim is simply straight forward from the body of the person wearing the camera. As the theorist Claire Colebrook puts it, “What makes the machine-like movement of the camera so important is that the camera can ‘see’ or ‘perceive’ without imposing concepts.” And it’s just this lack of “imposing concepts” that makes the body cam so powerful. Already, the defense attorney for Ray Tensing, the police man who killed Sam DuBose, is arguing for his own narrative about what we are seeing—or what he thinks we should be seeing—in the video.

This tension between seeing and believing is central to cinema history. Film noir, for example, famously played with the differences between what we see and what we say about what we see, as in Double Indemnity (1944), where we listen to the dying Walter Neff’s confession about his doomed murder plot while watching what “really” happened, opening gaps between what Neff says happened and what we think we see happening. The most famous case of all might be Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941), where the story of Kane’s life is told from multiple points of view, juxtaposing the testimony of different people who knew Kane with stylized visual depictions of these memories—except of course when the visual material depicts actions that none of these narrators could have known.

With the body cam video of the murder of Sam DuBose video, along with a growing proliferation of other videos such as the smart phone footage of the murder of Walter Scott by a police officer in South Carolina, we are seeing the power of this cinema of everyday life to challenge longstanding dominant narratives about the relationships between police and the African American community. The history of cinema is in part the history of the increasingly widespread presence of the motion picture camera in day-to-day life, from home movies to security cameras to the Apple phone. This expansion of cinema has itself developed a dual relationship towards the concentration and dispersal of cultural power, as the camera can both erode our privacy in the form of closed circuit surveillance videos but also serve as new forms of political resistance. In the case of the body cam, we have the technology of digital video operating potentially in both modes at once, as the eye of the police and as an eye on police.

As the video records that make up the cinema of everyday life enter the digital communication network, they become a part of a vast, unruly, and energetic cinematic screen culture involving arguments about interpretation and meaning carried out on news web sites, on blogs like this, and in the rough and tumble of the comments sections. Everyday cinema is by definition less decorous and polite than “official” cinema, with its business structures and organized and authorized forms of critique and study (such as a textbook like Screen Ages), but this difference has again always been a part of the legacy of American cinema, a tension between a new, impudent, popular art form and established cultural hierarchies of propriety, status, order, and power.

Ryan Coogler’s powerful 2013 movie Fruitvale Station evokes this dimension of the cinema of everyday life as he tells the story of the police murder of Oscar Grant in an Oakland, California BART station on New Year’s Day in 2009. Occurring just two years after the iPhone made movie technology a part of everday life, the killing of Oscar Grant became a national scandal after several witnesses recorded the incident and the videos became widely available on the Internet.

As the body cam video of the murder of Walter DuBose shows, cinema has always been more than just entertainment or diversion; it is also intimately connected to issues of justice and power. As DuBose’s sister Terina DuBose Allen puts it, “’I think that if there had not been a body camera, that Sam would have been left with the memory of everyone saying he was basically trying to kill a police officer,’ she said. ‘They would have turned a nonviolent man who was loved into a poster child for violence against police officers.’” It’s hard to come up with a more effective testimony to the power of everday cinema.