Last Sunday the long-time movie critic and scholar J Hoberman had a piece in the New York Times about “A Road Three Hundred Years Long: Cinema and the Great Migration,” a film series at the Museum of Modern Art that looks at movies related in some way to the Great Migration, the name historians assign to the movement of almost two million African Americans from the rural south to the urban north during the first four decades of the 20th century. His article focused in particular on examples of cinema made by black filmmakers that “defy characterization,” especially movies he says might be called “gospel cinema.”

Hoberman’s article, the film series at MOMA, and of course the movies he writes about point to so many different, important, and fascinating aspects of American movie history: the ways that history has participated in the construction of race and the mechanisms of American racism; the study of African American cinema in the first half of the 20th century; the role of spirituality in film. But today I want to focus on his suggestion that many of these movies “defy characterization” in order to think about how the multiplicity and variety of our screen experiences—the different contexts in which we encounter and watch movies—demonstrate the power of characterization and the importance of context in how we make sense of what we see and hear on the screen.

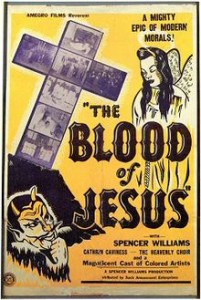

Hoberman mentions a number of intriguing movies in his article, but he spends the most time discussing The Blood of Jesus, a 1941 movie written and directed by Spencer Williams, who would became most well known to white audiences for his portrayal of Andy in the television version of Amos ‘n Andy in the early 1950s. Amos ‘n Andy has a history almost as fraught as The Birth of a Nation. The show was created as a radio version of a minstrel show by the white comedians Freeman Cosden and Charles Correll in 1943 who played the title characters, two supposedly African American friends living in the urban black community of Harlem. The show traded off of the racist stereotypes of the minstrel show and was immensely popular. When the show was brought to early television, black actors were cast, including Williams as Andy and Alvin Childress as Amos. The show thus became the first TV sitcom to feature a largely black cast, but as with Hattie McDaniel and Butterfly McQueen in Gone With the Wind, this visibility came at the price of reinforcing stereotypes about black life and culture.

But The Blood of Jesus seems a very different experience than Amos ‘n Andy. Set and shot in rural east Texas, The Blood of Jesus is a movie about rural black life with a strong evangelical mission. The movie tells the story of Martha, a young woman recently baptized who is accidentally shot when her non-believing husband Ras drops his gun. As she hovers between life and death, her soul travels to the big city where she is tempted by Satan (a character in the movie) and the promise of pleasure in the form of pretty clothes, seductive music, and easy money. In the end, she is rescued by an angel and (literally) the blood of Jesus and is miraculously healed.

The hour-long movie was made for $5000 by Williams for Sack Amusement Enterprises, one of the most prominent movie companies aimed at black audiences. Alfred Sack, the white owner of the company, said The Blood of Jesus was maybe the most successful “black” movie of the time. It played in both movie theaters (whether those aimed at black audiences or in segregated screenings at “white” theaters) and in churches across the country. Other than Williams, the rest of the cast were amateurs, many drawn from the Reverend R.L. Robinson’s Heavenly Choir, who perform several gospel standards in their entirety during the movie.

But don’t take my word for it. This is 2015, after all. You can watch any or all of The Blood of Jesus right here or on YouTube, which brings me to the question of why Hoberman might say this movie can “defy characterization.” In his article, he notes how the movie seems to call on a variety of cinematic traditions. In some ways the movie seems almost like a documentary, framing scenes of a rural baptism like a pictorial tableau, including those performances of whole gospel songs.

At the same time, The Blood of Jesus also incorporates “Hollywood” affects, such as the use of double exposure and other special effects. That documentary-style baptism is capped by a bit of comic shtick, as a reluctant convert flees in mock horror from what he says is a snake in the river. The movie is also a kind of musical in more ways than the prominent use of gospels and hymns. In the big city, we see Martha enjoy jazz dancers and a blues singer in a low rent nightclub. The movie makes clear that while blues and juke joint music are clearly the works of Satan, they are nonetheless extremely entertaining (otherwise they wouldn’t be temptations).

The upshot of these multiple influences is that many contemporary viewers don’t know what to make of the movie. Both Hoberman and the documentarian Thom Andersen, for example, appreciate what they see as Williams’s almost avant garde filmmaking techniques, but Hoberman also notes that others have referred to the movie as “folk cinema,” suggesting that Williams can be seen as a kind of naïve amateur, artlessly reflecting a rural black life far distant from Hollywood sophistication or cynicism. If you just read the reviews on the Internet Archive page on The Blood of Jesus, you can see more evidence of how viewers struggle with “characterizing” the movie. Is it a Christian movie? A historical record of rural black life in the early 1940s? An anti-racist polemic? A work of art or a complete mess?

I want to suggest, in keeping with the approach of Screen Ages, that what these different responses point to is not just a movie that defies characterization but also the ways in which all of our experiences of and responses to a movie are shaped by what we expect and assume about that movie. And these expectations and assumptions have everything to do with the context in which we encounter the movie. It is this context that frames the movie, that already prepares, informs, and subsequently constructs our experience of the movie.

Watching The Blood of Jesus on YouTube after reading an article in the New York Times or first encountering it in an auditorium at the Museum of Modern Art might prepare us to watch the movie as a work of historical and cinematic significance, a different framework than that experienced by audiences introduced to the movie in their local church. Whether the name Spencer Williams means nothing to us or triggers an association with Amos ‘n Andy creates two different sets of screening assumptions, just as each piece of information we might learn about his extraordinary life—his early life in vaudeville, his service in World War One and world travels, his apprenticeship in the early movie business, his work as a comic actor—transforms how we see the movie, and in a very real sense change the movie for us.

Part of the excitement of studying American movie history comes from encountering movies that maybe don’t so much defy characterization but have escaped characterization in the sense that they haven’t been made a part of a dominant narrative about the American screen ages. The Wizard of Oz, for example, a movie easily as curious and strange as The Blood of Jesus, has been so firmly embedded in the story of the “Golden Age” of Hollywood and the genres of mainstream moviemaking that much of it’s weirdness has been hidden to us. If you don’t know The Blood of Jesus, now is a great opportunity for a screen experience that defies characterization—or that can cause us to question just how we characterize any of our screen experiences.