As someone who grew up in southern California, the subset of disaster movies featuring killer earthquakes have always had special meaning for me. (And a quick reality check for the rest of the country: how many places in the United States immune to earthquakes? Zero. Don’t feel too cocky, America). In Chapter Six of Screen Ages, I write about the disaster movie trend in Seventies American movies in general, but on the occasion of the premiere of San Andreas (Peyton 2015), the latest movie depicting/celebrating the total destruction of my hometown, I want to use the earthquake movie to ask a very particular question about the disaster movie: who is starring in them and why?

First, a quiz. What do these three actors have in common?

The answer: each was the star of an earthquake movie in a different screen age of American movies: Clark Gable, the star of San Francisco (Van Dyke 1936), Charlton Heston, the star of the Seventies “classic” Earthquake (Robson 1974), and of course Dwayne (The Rock) Johnson, the star of San Andreas. As the stars/leading men in these movies, all three are at the center of plot lines that hinge on the importance of male agency, the idea that catastrophic disasters provide an opportunity for men to test and prove themselves. By so doing, they also demonstrate the importance and centrality of masculinity, or at least a certain definition of masculinity. As times change, however, we can see how those definitions change in ways that speak to larger cultural tensions and (I can’t resist) fault lines about how we understand gender roles.

In a very basic sense, the appeal of the disaster movie genre is literally obvious: nothing is more visually arresting and exciting than scenes of widespread destruction. The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 was one of the first national disasters of the first screen age, and early movie companies such as Edison were quick to send camera operators to record the carnage:

At the same time, other movie companies were quick to come up with recreations of the disaster, as in this reenactment from the American Mutoscope and Biograph company showing the burning of a scale model of the San Francisco skyline. It’s likely that when the film was marketed to audiences, the line between the real and the reenacted was left deliberately unclear:

Thirty years later, Gable, an epitome of onscreen masculinity in 1930s American movies, starred in San Francisco, a melodrama about the rakish owner of a saloon and music hall played by Gable who competes for the attention of a trained opera singer (Jeannette MacDonald) with the son of one of the city’s wealthiest families (Jack Holt). This romantic and class struggle is interrupted by a struggle for survival as the earthquake hits just as Gable’s and MacDonald’s characters have a big fight:

In the end, Gable’s rival is (conveniently) among the quake’s victims and both the lovers and the city are reunited as the entire community comes together across lines of race and class, determined to rebuild San Francisco. The film betrays its Depression-era origins in arguing for an end to social divisions in the face of a great disaster, and Gable himself was a leading man for the times: a bit of a rascal and a bit of a cynic about the system, a rebel who challenges the dominant values of the society up to a point, but who finally falls in line when the chips are really down.Gable was 35 when he starred in San Francisco.

Forty years later, 1974’s Earthquake actually featured several potential stars. In keeping with the disaster movie trend of the times, it was an ensemble movie featuring a range of character types. Top billing, however, went to Heston, 51 when the movie was made. An example of stiff-jawed 1950s American masculinity who had played both Ben-Hur and Moses, by the 1970s Heston was still a major star, but a star definitely of an older generation. In the same year that a 37-year-old Jack Nicholson was playing the anti-hero main character in Chinatown (Polanski), another cynic who reflected the social disillusionment of the Vietnam and Watergate eras in a movie set in the Depression, Heston’s portrayal of a middle-aged construction engineer trapped in an unhappy marriage with a wife played by another star of the 1950s, Ava Gardner, suggests an old-fashioned masculinity out of step in 1970s America. In the movie, he begins an affair with a young single mother played by a 32-year-old Geneviève Bujold, only to have his own story interrupted by a massive quake leveling Los Angeles. The following clips convey the damage done (as well as some cheap-o 1970s special effects, including a toy truck full of plastic cows and actors pretending to sway while a camera shakes), but they can’t recreate the effect of Sensurround, the in-theater effect created by huge speakers pushing the bass sound to enhance the sense of the world shaking:

Rather than triumphing over the collapse of Los Angeles—or the collapse of old Hollywood—Heston’s character dies in the end when he foregoes a life with his new lover in order to try and rescue his wife.

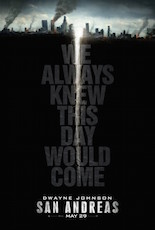

So what does Dwayne Johnson tell us about the stories we are telling ourselves about masculinity in 2015? On the one hand, we now have some one other than a white guy saving the day; on the other, it’s still a guy. While his wrestler background gives him something of Gable’s roguish quality, and while his troubled marriage in the movie may suggest the social instability at the heart of 1974’s Earthquake, Johnson’s goal in San Andreas is to save all the women in his family (both his wife and daughter) and reunite the nuclear family. And Johnson’s physical expression of masculinity continues a trend begun thirty years ago with actors like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone: bulked up and buffed up action figures who are almost parodies of manly masculinity. At the same time, part of Johnson’s likability as an actor stems from his self-awareness that there’s something ridiculous about a six-foot, five-inch workout enthusiast portraying an average Joe family man.So, are we looking at a story about wiping out LA (most of California, actually) and returning to a more traditional kind of American masculinity, although maybe with slightly more ethnic complexity? Or is San Andreas so postmodern that all of the characters and situations come with quotation marks already firmly in place, suggesting it’s all just an excuse for 100 minutes of costly but entertaining CGI? In any case, make sure you have your own escape plan ready, just in case.