A headline in the September 7 New York Times points to “The Crowding-Out Effect of Gargantuan Movies” on the final box office numbers for the just concluded summer movie season. While the overall take for ticket sales was up over 10% for 2015 over 2014, the real story, according to this article, was how a small number of megahits–Jurassic World, Inside Out–made up for the large number of underperforming blockbuster-wannabes like The Fantastic Four and The Man From UNCLE. Speculation was already underway in Hollywood on whether this disturbing (at least to studio executives) new trend might continue:

It may only get worse: In the summer of 2017, for instance, Disney has new installments from its “Toy Story,” “Pirates of the Caribbean,” “Guardians of the Galaxy” and “Star Wars” franchises opening back to back. That lineup is expected to leave little room for anything else to bloom.

But what does this mean for the average movie fan? How should those of us mainly on the ticket-buying–and streaming-service subscribing—feel about this “crowding out effect”? As many have remarked before me, the advent of television shows and web sites devoted to covering the business of media have made movie fans the world over participate in the weekly anticipation of which new release will “win” the opening weekend at the box office. Movie advertising as well has a long history of selling movies on the basis of their ticket sales.

While it might not be surprising that a story in the “Business” section of the Times makes the automatic association between box office revenue and movie success as the most important indicator of the state of American movies, in the age of multiple screen experiences, video streaming, and niche marketing, maybe it’s time to begin asking, “is the era of using box office results to measure success in the movies coming to an end?”

By this question I don’t only mean to make the obvious point that just because a movie sells doesn’t mean it’s automatically a “good” movie (the reverse corollary also holds true: just because a movie sells doesn’t mean it’s automatically a “bad” movie, either). I mean instead to ask whether even from a business perspective of profit and loss, box office sales may be past their sell date as a marker of the health of the movie business, both as a business and as an art form.

The quick answer to such a question is probably, “are you out of your mind?” The very story that prompted this entry is evidence both of how much ticket sales still dominate the movie business and of how Hollywood’s financial reliance on the summer blockbuster, a trend now stretching back forty years to the summer of Jaws in 1975, seems in no obvious danger of going away. Quite to the contrary, in fact: Marvel Studios has announced their release plans for their (guardians of the) galaxy of franchise movies through 2019, and Warner Brothers has released their plans for DC Comics characters and Harry Potter movies through 2020. All these developments suggest that the Times story may be right. Maybe the real question to ask is whether the major studios will release any movies other than superhero franchise movies in years to come?

Such fears have now become their own Hollywood storyline, a dystopian narrative about a future world populated not by zombies but by endless clones of the same small group of fantasy characters. Two years ago, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg appeared together on a panel at the University of Southern California and speculated about what come next in the movie business, and they famously predicted what Spielberg called a “big meltdown” as the economic logic of the summer blockbuster—along with what The Times story refers to as the “crowding out effect”—finally collapses on itself. Both Lucas and Spielberg suggested a future where, in Lucas’s words, “going to the movies will cost 50 bucks or 100 or 150 bucks, like what Broadway costs today.” Most screen experiences, on the other hand, will take place as “video on demand” over Internet streaming services.

Such fears have now become their own Hollywood storyline, a dystopian narrative about a future world populated not by zombies but by endless clones of the same small group of fantasy characters. Two years ago, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg appeared together on a panel at the University of Southern California and speculated about what come next in the movie business, and they famously predicted what Spielberg called a “big meltdown” as the economic logic of the summer blockbuster—along with what The Times story refers to as the “crowding out effect”—finally collapses on itself. Both Lucas and Spielberg suggested a future where, in Lucas’s words, “going to the movies will cost 50 bucks or 100 or 150 bucks, like what Broadway costs today.” Most screen experiences, on the other hand, will take place as “video on demand” over Internet streaming services.

Most media outlets covered these predictions as “bad news” for the future of the movies, and to be fair the use of terms like “meltdown” and “implosion” certainly doesn’t sound upbeat. But maybe there are signs that the future is now. Video-on-demand continues to grow, and contrary to popular belief, the production of “indie” movies shows no sign of slowing down. Writing two weeks ago, also in The New York Times, Steven Johnson crunched some numbers to show that the number of financially successful “midsize” movies aimed at grown-ups has not in fact shrunk over the last fifteen years, and that “the total number of pictures released in the United States — nearly 600 in 2011 — remains high.” He quotes a report from website Techdirty.com called “The Sky Is Rising!” offering evidence that the doom-and-gloom claims of what they call the “legacy entertainment” are largely unfounded.

So what does any of this tell us about my original question: “is the era of using box office results to measure success in the movies coming to an end?” Neither the optimistic or pessimistic predictions outline above suggest that money will become a less important part of the movie business in the future, whether the sky rises or falls. But I’ll conclude by offering two examples of why box office receipts may become a less reliable measure of even financial success for the movies—or whatever we may call the myriad screen experiences of the future.

- The growing diversification of ticket prices is already complicating just what those box office numbers mean. The topic of movie ticket price differentiation has been in the air for a while now, as in this blog post from Steven Zeitchik in the LA Times. The basic model holds that rather than charging a single price for every seat in a movie theater for every movie, the price of a ticket could vary based on the popularity of a movie, its exhibition costs, etc. The rise of 3-D, IMAX, and luxury screening experiences has made differential pricing a reality. Action blockbusters are released simultaneously in 2-D and 3-D versions, in big screen and “regular” screen forms, each accompanied by a different ticket price. The result is that the same number of people going to see the opening weekends of Trainwreck or Ant Man would produce two very different box office numbers, depending on what version of Ant Man viewers bought tickets for. This practice hasn’t changed the importance of those opening weekend numbers for now, but it has skewed the list of all-time opening weekend records heavily towards contemporary, multi-screen experience blockbusters, potentially making these lists less relevant as measures of, well, really anything, even the financial acumen of the studios who made them.

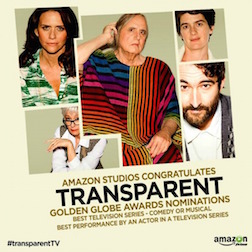

- Increasingly, who watches a movie is as significant as how many. At the same time that a smaller number of giant blockbusters are dominating the big screens, the other truism about our screen age is the increasing “nichification” of our cultural consumption. While Jurassic World aims at the widest audience possible, a streaming on-demand series such as Orange Is the New Black or Transparent is more concerned with cultivating a smaller but more loyal and devoted following, one that “over the top” content providers like Netflix or Amazon see as a valuable core market for their subscription services.

After all, “loyalty” is crucial to the business model of the subscription. In fact, one of the most notable aspects of these over-the-top services—the kind of screen experiences Spielberg and Lucas were pointing to as the future of movies—is the refusal of companies like Netflix and Amazon to disclose their viewership numbers. As this article from Variety demonstrates, this secrecy is driving people used to “legacy” models of measuring of movie and television success a little crazy. And of course an obvious reaction is to point out that if the ratings numbers were really great, these companies would be quick to publicize them. But maybe not. The point could also be to establish new business models, models based less on the viewership—box office numbers—of individual movies and shows and more on the “brand” identity of the content provider: “It’s Not Television, It’s HBO”; “USA: Stories Welcome.” In this way, companies such as Netflix hearken back to the branding of the classic Hollywood studios of the 30’s and 40’s or the early movie companies of the nickelodeon era, where moviegoers were encouraged to look for a luxurious MGM production or a “Keystone” comedy. Looking forward, maybe one of the meanings of Spielberg and Lucas’s predictions is that the day of the dominance of the box office numbers may be melting down along with the conventional movie industry.

After all, “loyalty” is crucial to the business model of the subscription. In fact, one of the most notable aspects of these over-the-top services—the kind of screen experiences Spielberg and Lucas were pointing to as the future of movies—is the refusal of companies like Netflix and Amazon to disclose their viewership numbers. As this article from Variety demonstrates, this secrecy is driving people used to “legacy” models of measuring of movie and television success a little crazy. And of course an obvious reaction is to point out that if the ratings numbers were really great, these companies would be quick to publicize them. But maybe not. The point could also be to establish new business models, models based less on the viewership—box office numbers—of individual movies and shows and more on the “brand” identity of the content provider: “It’s Not Television, It’s HBO”; “USA: Stories Welcome.” In this way, companies such as Netflix hearken back to the branding of the classic Hollywood studios of the 30’s and 40’s or the early movie companies of the nickelodeon era, where moviegoers were encouraged to look for a luxurious MGM production or a “Keystone” comedy. Looking forward, maybe one of the meanings of Spielberg and Lucas’s predictions is that the day of the dominance of the box office numbers may be melting down along with the conventional movie industry.