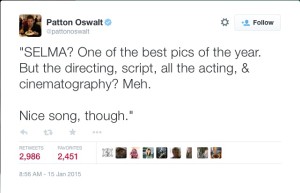

January 16, 2015

This tweet from the comedian (and serious cinephile) Patton Oswalt sums up many reactions to the often baffling logic of Oscar nominations: how could a movie such as Selma, a historical narrative based on the historic civil rights marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965, be nominated as one of the best pictures of the year but not receive nominations for the director of the movie, Ana DuVernay, or the movie’s lead actor, David Oyelowo, who has earned wide acclaim for his portrayal of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, surely one of the most daunting roles any actor could face? That the movie was directed by an African American women and features a largely black cast, along with the fact that no actor of color was nominated for any of the twenty major acting awards, points to Hollywood’s and the Oscars recurring problems with reflecting and addressing the diversity of American society and culture.

As Screen Ages illustrates, race and gender—and racism and sexism—have been central points of struggle within the history of American movies and how we construct that history, from the ways that prominent early women filmmakers such as Alice Guy Blaché and Lois Weber disappeared from mainstream movie histories until very recently to the reliance on racial stereotyping and prejudice exemplified most notoriously by D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (and especially its original title The Clansman).

To be sure, there have been other explanations offered for the surprising exclusion of DuVernay and Oyelowo from the Oscar slate, such as Paramount’s inability to distribute screeners (advance DVD copies) of Selma to most of the major guilds ahead of awards season (to those outside of the movie industry who have to pay to see movies, this may seem like a silly problem, but many Oscar voters expect to able to review movies for free at home).

As the director Spike Lee points out in an interview in The Daily Beast, however, the pattern represented by the snub to Selma is not a new phenomenon, and echoes the circumstances surrounding his 1989 classic Do the Right Thing, which as is detailed in Chapter Seven of Screen Ages was passed over as a Best Picture nominee in a year when the eventual winner was also a movie about American race relations, the much more sentimental Driving Miss Daisy. As Lee bluntly (and correctly) notes in his words of advice to DuVernay, in spite of this omission Do the Right Thing continues to be regularly taught and written about, while Driving Miss Daisy has largely faded from consideration of the most influential films of the 1980s.

The history of the Academy Awards itself as an institution is another factor as well. You could argue, in fact, that part of the purpose of creating the Academy Awards was to limit diversity: in aligning the existing craft guilds with different Oscar categories, part of the purpose of the awards was to counter labor organizing efforts by offering the chance for elite recognition by the august-sounding “Acadmey of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.” If the diversity of the work force remains an issue in the movie industry at large, the problem is especially egregious among the Academy voters, who according to this Atlantic Magazine article are 94% white, 76% male, and whose average age is 63 years old: hardly a representative sampling of America. The Academy is now led by Cheryl Boone Isaacs, the first black woman and only the third woman to serve as president; her early comments have defended the nomination process so far.

This is a story that will continue to develop as the Oscar ceremony approaches, and this is exactly kind of issue that demands a critically informed historical perspective. One of the key goals of Screen Ages is to help its readers to frame their own answers to the question implied by Patton Oswalt’s appropriately exasperated tweet about the perpetually exasperating history of the Oscars.